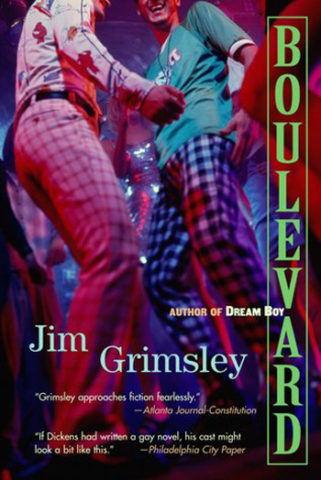

Boulevard

Boulevard

by Jim Grimsley

Published by Algonquin Books

Published April 19, 2002

Fiction

304 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

March 27, 2002

Jim Grimsley’s lyrical and explosively violent first two novels, Winter Birds and Dream Boy, have something of a cult following. Both portray brutalized, poor, rural, sensitive Southern boys. Grimsley consolidated his reputation as a Southern Gothic writer with My Drowning, told from the perspective of a brutalized Southern girl. In Comfort and Joy, he moved from writing about poor Southerners in the countryside to poor Southerners in cities and writing about a poor Southerner (Danny, the hemophiliac protagonist of Winter Birds) who had made the rural-urban migration.

Boulevard (2002) opens with Newell, a recent graduate of high school in Pastel, Alabama, arriving with his small life savings in New Orleans, a city that seems big but not at all easy to him. There have been many stories of naïfs arriving from the countryside and being swallowed into the vortex of the ecstasies induced by readily available sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll that John Rechy called “the city of night.” Often in reading books in this genre, I wonder how the youth being swept away pays the cover charges and pays for drinks and drugs, as well as for food and rent. Grimsley shows generating income as a major problem for Newell.

On his first day, he finds a room with a bath above a junk store in the French Quarter, but a month’s rent plus a security deposit takes most of his money. Subsisting on (unheated) cans of soup, he makes the rounds of businesses that placed help wanted ads in the newspaper, leaving many applications. Grimsley effectively chronicles Newell’s desperation as his money is running out and he is afraid he will have to retreat back to Pastel.

Although he has the return bus fare set aside, shortly before he has to use it, his good looks get him a job as a busboy in a gay restaurant. After a few weeks, he loses the job for spurning the manager’s advances. After another financial panic, he finds a niche in a porno bookstore. The store’s straight manager lets Newell take over display of the store’s mostly gay products, then of labeling the gay films in the quarter peepshow booths, and, eventually, of choosing which ones to screen. Newell quickly becomes the star of the store. His worshippers include Henry, a doughy young government employee who shows him around the gay cruising venues of New Orleans Anno Domini 1978, and the store’s old and unattractive transgendered “cleaning lady,” Miss Sophie (né Clarence Eldridge Dodd).

Newell enjoys the pornography he watches and is attracted to a husky type much represented in gay porn. Nonetheless, he has a nearly chaste life—at a time and in a place when opportunities for casual sex seemed limitless. Not counting Henry’s quickly abandoned attempt to go down on him, Newell has sex with three men, including an s&m scene that greatly scares him. Two of the three (including the extreme s&m master) are bisexual. The only gay one, a drug-loving historian of old New Orleans families like his own, Mark Duval, is Newell’s lover for a time (though that time is skipped over in the novel and its duration is not even mentioned).

Despite feeling attractions to self-annihilation, Grimsely’s protagonists usually escape (albeit narrowly) their dangerous human predators, whether these are family members, lovers, high school classmates, or (as herein) nearly a stranger (Jack, the bisexual sadist is living with an intimate female friend of Mark’s and is also the nephew of the owner of the porno store, but Newell does not know the store’s owner).

There is plenty of foreshadowing of extreme sadism, particularly an episode with slaves about which Mark has found documentation in old family papers, and Grimsley skips over what happened in Newell’s scene with Jack, just as he skips over Newell’s weeks or months as Mark’s trophy partner.

The changes in perspective (including from Jack to Newell in the last and shortest chapter) seem gratuitous to me. Having created a credible young female character in My Drowning, Grimsley does not need to prove that he can make various perspectives credible. The shifts in perspective from Newell to his landlady’s appraisal of him advance the narrative, but the lengthy switch to Miss Sophie’s stream of (semi-)consciousness does little to advance the narrative and strike me as showing off (or, perhaps, a misguided homage to The Sound and the Fury).

Verisimilitude problems

I also balk at the idea that one can learn the skills of fellatio entirely from watching porno films. There was a dearth of anticipatory socialization for proto-gay boys (and girls) in the era in which Newell grew up, especially in the rural southern United States. Closely scrutinizing pornography was (and is) a partial remedy for this, but the mechanics of fellatio are not visible and I find it very difficult to believe that Newell could have had exceptional skill in his first try (on a partner not lacking in experience and expectations of skillful performance). Almost as difficult to believe that Henry was so inept. Practice may not make perfect, but the Henrys of the gay world rely heavily on their skills as fellators.

Having moved to a gay Mecca myself in Anno Domini 1978, I also question the simultaneity of Alicia Bridges’s “I Love the Nightlife” and Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive.” They were both disco bunny anthems (though Newell lacked the experience that made Gaynor’s resonate for many of us). I am completely sure that Gerald Ford was not president in 1978. There is no particular need to have specified who was president, but to make a point of doing so twice and to get it wrong is astounding. That Jimmy Carter was elected in 1976 (so that he took office in 1977) is not a particularly arcane fact. It is a howler that should not have slipped by a copyeditor (or have been made at all).

Conclusion: Boulevard within Grimsley’s growing ouevre

Despite some failures of plausibility and irritating shifts of perspective, I found Boulevard an engaging portrait of a young southern boy from the country discovering a wider world—some of the variety, some of the excitements, and some of the perils of the exploding urban gay scene for a 1970s Candide. Although the prose is less incantory than that in his first books, the dialogue is not as stilted as that in Comfort and Joy, and the narrative is considerably terser than Kirith Kirin, closer to the compression of Grimsley’s first novels—with some lyrical passages about the sights and smells of New Orleans. A position in academia (at Emory University) does not seem to have made Grimsley play safer in topics. Neither has it imbued him with the need to fact check even when writing about the relatively recent past.

Author Q&A

Wearing a green plaid shirt (not the standard-issue authorial black), Grimsley (1955–) was in the tenth city in ten days on his Boulevard tour and a bit tired. He read from Miss Sophia’s part (all of the parts: he is a playwright!). I said that although I found Miss Sophia a convincing character, I didn’t see why she took over (for a while) narration. He said that Newell was not sufficiently (internally) conflicted a character to maintain interest as the narrator (for the reader, though, I suspect for the author more so). His plan from the beginning was for Newell to discover New Orleans in the first half and for New Orleans to discover Newell in the second.

I had been planning to challenge learning fellatio technique from watching porn, but on his own he said that in the South then (and largely now) porno stores were where many young gay men learned what to do, as Newell takes up toys he has never seen before. (I think that one might learn positions in which to perform fellatio and that it exists from watching but that good technique cannot come from that alone.)

Grimsely himself came out in Chapel Hill but moved to New Orleans at the time Newell does (1978).

Currently, he has a science fiction book [The Ordinary] overdue for delivery and has been writing a play commissioned from a Chicago theater, About Face, at which he is playwright in residence. They asked for a play about a serial killer [Fascination], and he says what he has written is about the fascination (and magnification) of serial killers, who are far from being the supermen of popular representations. He plans to write a nonfiction meditation on school desegregation in the south, which he lived through [How I Shed My Skin].

Someone asked why he was thought of to write about a serial killer. He thinks that he writes about reality. He was particularly exercised at Francine Prose claiming that My Drowing was exaggerated. He said that everything that happens in that novel is something he heard female relatives telling each other when they didn’t know he was listening. He stressed that poverty is not ennobling, that the happy acceptance of their lot is a myth, and the dehumanizaiton is far more common.

published by epinions, 27 March 2002, 16 May 2003

©2002, 2016, Stephen O. Murray