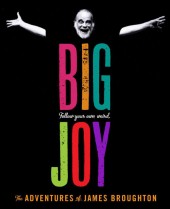

Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton

Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton

Directed by

Stephen Silha and Eric Slade

Review by Stephen O. Murray

Released: March 9, 2013 • 82 min.

October 8, 2015

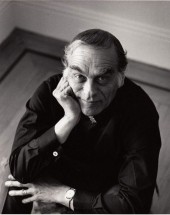

I had been aware of poet/avant-garde film-maker James Broughton (1913–1999) for a long time without ever reading any of his poetry or seeing any of his films. He published many books; I had not had many opportunities to see any of his films, though there is now a three-DVD collection of them that I have sampled.

The documentary Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton (made by Eric Slade, who made a documentary on Harry Hay, Hope Along the Wind, broadcast on PBS) has vignettes from many of Broughton’s films — including too much nudity to ever make it onto American Masters. This is too bad since it is a very good documentary with lots of images of and from him, some poetry (that does not grab me), and the saga of an interesting life.

It started in Modesto. In California’s Central Valley, Broughton provides another example of a gay man who was not tight with his mother and came to despise her (others include Edward Albee, Scott O’Hara, Gore Vidal). His father died in the worldwide Spanish influenza pandemic that followed the First World War.

Broughton moved to San Francisco’s North Beach, the coffeehouses of which featured poetry reading (sometime marathon multi-poet ones) during the 1950s with Broughton, Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, and others, before the Beats with their marketing genius Allen Ginsberg.

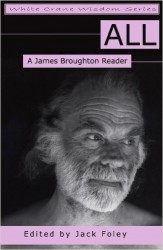

Larwence Ferlinghetti, the poet and owner of City Lights Bookstore, who was arrested for the alleged obscenity of Ginsberg’s Howl, is one of the writers who speaks on camera about Broughton. Others whom I recognized (oddly, tags identifying interviewees only begin appearing more than ten minutes into the 82-minute running time) are Armistead Maupin and Kevin Killian, his colleague George Kuchar, and Jack Foley who edited All: A James Broughton Reader in 2007.

Larwence Ferlinghetti, the poet and owner of City Lights Bookstore, who was arrested for the alleged obscenity of Ginsberg’s Howl, is one of the writers who speaks on camera about Broughton. Others whom I recognized (oddly, tags identifying interviewees only begin appearing more than ten minutes into the 82-minute running time) are Armistead Maupin and Kevin Killian, his colleague George Kuchar, and Jack Foley who edited All: A James Broughton Reader in 2007.

It is not clear to me why Broughton stopped making films for some time after winning a special prize for “poetic cinema” (for The Pleasure Garden) at Cannes, bestowed upon him by Jean Cocteau, or why he decided to get married in 1962 (to Suzanna Hart). He had earlier (1948) fathered a child with Pauline Kael and would father three more, though he had also had a long-term relationship with one man (primarily theater director Kermit Sheets), and in 1975, at age 61, would begin another with 26-year-old filmmaking student at the San Francisco Art Institute, Joel Singer, that he would celebrate in verse and film until his death a quarter of a century later.

Both widows speak to the camera, the female one still very pained at being left, the male one rueful about the downside of loving someone 35 years older (but grateful for the time they had together).

Broughton himself stated that before he met Singer, “I was on the point of feeling my life was over, my life in the suburbs was routine. Joel has actually extended my life by giving me a tremendous shot in the arm or rebirth, re-enthusiasm and delight in the world. He’s half my age. It means, I associate with his friends who are all in their 30s and so suddenly I felt I was the same age I was when I began making films 40 years ago.”

Broughton himself stated that before he met Singer, “I was on the point of feeling my life was over, my life in the suburbs was routine. Joel has actually extended my life by giving me a tremendous shot in the arm or rebirth, re-enthusiasm and delight in the world. He’s half my age. It means, I associate with his friends who are all in their 30s and so suddenly I felt I was the same age I was when I began making films 40 years ago.”

Though there are lots of talking heads and some words displayed (as in Baz Lurhman’s film of The Great Gatsby), there are a lot of images, including sequences from The Bed (1968) and Devotions (1983) and a trove of archival photographs and home movies.

©2016, Stephen O. Murray

Film Link •Trailer •imdb •Amazon