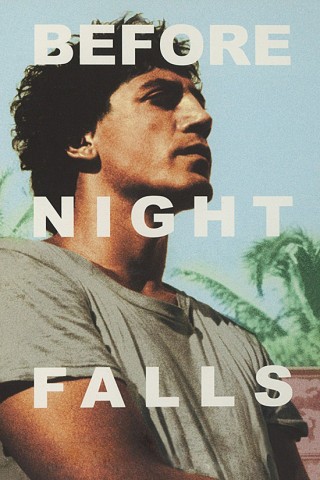

Before Night Falls

Before Night Falls

Directed by Julien Schnabel

Released February 23, 2001

Drama (history/biography)

133 min. • Find on imdb

Review by Stephen O. Murray

January 4, 2001.

I think that Julian Schnabel’s film of Reinaldo Arenas’s memoir, Before Night Falls, is a great film. Inevitably, much of the book is missing, but its essences and most of its themes survive. The film is not as raw—sexually or otherwise—as the book, but had Arenas lived longer, the book might have been less raw, too.

Schnabel (who is credited with coauthoring the film script) chose to illustrate something that it would not have occurred yo me to include in a movie adaptation: Arenas’ typology of Cuban homosexuals—a typology in which he himself did not fit. This unlikely material fits in smoothly and probably helps audiences unfamiliar with the homosexual subculture under the repression by Castro’s regime with its block-level surveillance of any “counter-revolutionary” activity.

Although there is hardly any sex in the film (except for one very brief part of illustrating the typology), the film is suffused with sensuality and sexuality. Just the nonjudgmental representation of so flamboyant a homosexual is shocking to some Americans, but there is one relationship in which more sexual detail definitely is needed. The whole point of “Who’s the man?”/ “You’re the man, because you know judo” exchange is that the bisexual man who is more conventionally masculine in appearance (the one who knows judo) was penetrated by the somewhat effeminate entirely homosexual one.

Fumbling that, and not making that the “pink brigade” was gender- and sexual-“deviant” individuals forced slave labor in inland concentration camps sufficiently clear, are the only faults Iinto ind with the adaptation. I loathe Julian Schnabel’s paintings for, among other things, their ugliness. The cinematography done by Xavier Pérez Grobet and Guillermo Rosas is beautiful to look at, even when what is being shown is not beautiful. The images flow very well, too. There are many beautiful tropical compositions, but these never seem like stills. Indeed, the camera is rarely still. I’m tempted to compare The Thin Red Line for the visual lushness, but unlike Terrence Malick’s film, the images in Before Night Falls are not a substitute for narrative development. What one sees on the screen advances the storyline and/or provides insight into the character Reinaldo Arenas and how he saw the world, first the tropical paradise of Cuba turned into totalitarian hell and then the beauties and squalors of Manhattan.

The very international cast, including Schnabel’s son as a teenage Reinaldo, are also excellent. Sean Penn’s accent is strange, but he does what needs to be done in the very small part he plays. The heterosexual Spanish actor Javier Bardem has to play a very complex homosexual character in sickness and health (and drug-crazed and zombified by solitary confinement). And he has to play it in English and, what he has said was even more difficult for him, Cuban Spanish. Oh, yes, and he also has to be credible as a writer, because this is the rare biopic about a writer in which the writing is actually important.

(Bardem won the Volpi Cup at the Venice Film Festival, the Independent Spirt Award and National (US) Board of Review’s award for best actor, and was nominated for Golden Globe and Oscar best actor awards.)

IMO, the most attractive man in the film is the French actor Olivier Martinez as Lazaro, whose American experiences are the basis for Arenas’ novel The Doorman. The Italian actor Andrea Di Stefano plays the viciously self-absorbed bisexual collaborator with the regime, Pepe Malas. The ever-adventurous Johnny Depp is used to illustrate the point that machista (the prison commandante) and drag (Bon Bon) are two sides of the same coin (machismo).

Besides getting Depp and Penn in small parts, Schnabel also enlisted Brazilian director Hector Babenco (Pixote, Kiss of the Spider Woman) and Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski to play Arenas’ mentors, the martyred Cuban writers José Lezama Lima and Virgilio Pinera. Canadian actor Michael Wincott is Herberto Zorilla Ochoa, the writer put on a show trial to condemn the crimes against the revolution of artists. [Plus Diego Luna as Carlos.]

Fidel Castro plays himself in various archival footage. He is the #1 villain in Arenas’ book (followed by Gabriel García Marquez). He remains that in the film, but a fairly remote one.

As I suggested above, the horror of the treatment of homosexuals in the concentration camps is insufficiently clear in the film. I think that using the swooningly elegiac adagietto of Mahler’s 5th Symphony to accompany the images of crackdown followed by shots of the slave labor at the edge of a sugarcane field burning ever-so photogenically prettifies the concentration camps. (Besides, the Mahler adagietto is as associated with Death in Venice as “Thus Sprach Zarathustra” is with 2001. I don’t think that it is available for new associations.) In contrast, overdubbing the walk along the seashore with Lou Reed’s woozy “Rouge” (played by Laurie Anderson) works perfectly.

Schnabel has downplayed the sexual graphicness of the book, but as important as pursuing sex was to Arenas, freedom was what he most ardently sought. He had to write, and he had to write his way. The film shows this compellingly, and much more.

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

first published on epinions 4 January 2001