Bad Education

Bad Education

Written and Directed by Pedro Almodóvar

Released March 19, 2004

Drama (foreign/Spain)

106 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

January 5, 2005.

Pedro Almodóvar’s movies have been among the most popular non-English language movies in America for the last decade and a half, with Todo sobre mí madre (All About My Mother) surpassing even Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervíos (Women on a Verge of a Nervous Breakdown) as a commercial success here.

Personally, I liked Almodóvar’s earlier, wilder movies with Carmen Maura and/or Antonio Banderas more than the more strictly controlled international hits All About My Mother and Talk to Her (Hable con ella).

Mala educación (Bad Education) is also formalist rather than anarchic, with more than a hint of the look and sound of an Alfred Hitchcock thriller: especially the music of the opening credits and the appearance of a stranger claiming to be someone the movie’s protagonist, Enriquè Goded [Fele Martínez, who played the young Otto from Lovers of the Arctic Circle], used to know. [1]The temporarily blocked film director has a name that is more than an alliteration of the name of the never-blocked auteur Jean-Luc Godard. The stranger [international heart-throb Gael García Bernal, whom I regard as the Mexican Johnny Depp in his fearless embrace of way-out-there roles] says that he is Enriquè’s first (and, it is clear, greatest) love, Ignacio, but insists on being called by his stage name, Angel.

The movie seems to me to draw on John Grayson’s Lilies, with less stylization. At least both movies are centrally concerned with now-grown-up pupils forcing priests (and ex-priests) to confront not only their molestation of young boys but their ex-pupils anger at interference with their first loves (for other boys).

The movie seems to me to draw on John Grayson’s Lilies, with less stylization. At least both movies are centrally concerned with now-grown-up pupils forcing priests (and ex-priests) to confront not only their molestation of young boys but their ex-pupils anger at interference with their first loves (for other boys).

Bad Education has art/set decoration [by Antxón Gómez, who also did All About My Mother and Talk to Her] that is hard not to notice (often saturated red), but Bad Education is less stylized than Lilies. In part, this might be because Lilies involves staging the past (as part of the revenge) whereas Enriquè has become a film-maker and sets out to film the story that Angel brought him in the first scene.

There is a lot of plot, more so than in any other Almodóvar movie I can remember. Almodóvar plots always have twists and turns and revelations that should not be described to persons who have not yet seen the movie (in this it resembles Zhang Yimou’s Hero and House of the Flying Daggers but with no heterosexual romances and no CGI effects).

The priestly molestation part of the movie is set in the Franco era, when the power of the Roman Catholic Church was close to being absolute—and when Almodóvar was a schoolboy. (The movie’s story about the blurring of fiction and memory is complex enough without speculating what, if anything, derives from Almodóvar’s observations and experiences as a schoolboy!)

The present of the movie is set in 1980, after the rapid social changes in Spain that followed the death of the dictator. These included a considerable loss of authority for The Church, though covering up sexual abuse by priests around the world continued into the third Christian millennium (and the emergence as a film-maker of Pedro Almodóvar). It is left for viewers to judge the extent of retroactive complicity for his own professional profit of the film director Enriquè Goded. My own is that the pursuit of art (or, at least, of a compelling story) readily excuses complicity with crimes, at least in the view of the artists (/auteurs).

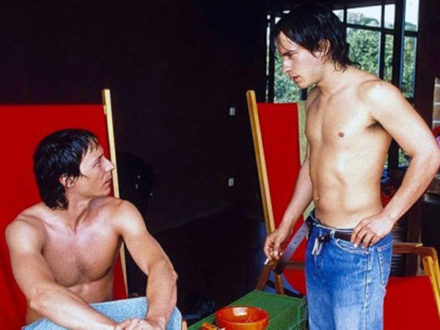

Gael García Bernal has an extremely showy part that includes playing a heterosexual actor who undertakes the part of a female impersonator and a sexually receptive homosexual (with longer scenes of simulated sex, but without any of the full frontal nudity of Y tu mamá, tambien). It is Fele Martínez, however, who received a European Film Award nomination for his troubled spectator/participant/ringmaster role as Enriquè. The actors playing the young Ignacio and Enriquè, and the younger and the older Father Manolo [Daniel Giménez Cacho and Lluis Homar, respectively] are also excellent. And Talk to Her star Javier Camara has a laugh-generating cameo part as Ignacio’s confederate.

At a key point in the plot, the former Father Manolo and Angel kill time in a ciné negro (cinema noir) revival. I don’t know which movies they see, but one of the posters they pass is for Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity. García Bernal’s Angel is more like the young enamorados in Our Lady of the Assassins than like Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity but has Stanwyck’s amorality and willingness to use good looks, while the Fred MacMurray part is split between Martínez and Homar (and no Edward G. Robinson is anywhere to be found).

Like With a Friend Like Harry, Bad Education lacks classical catharsis, and it may leave a taste of ashes for viewers eager to identify with Angel. (And those not paying attention might get lost in the labyrinthine plot.)

Aside from enjoying the showcasing of the talented (and, um, shall we say “hot”?) Gael García Bernal, Bad Education suggested to me that some of the spirit of playfulness is returning to Pedro Almodóvar after some rather mopey movies. For that, I’ll round up a 4.5 rating. But La ley del deseo (Law of Desire, 1987) is still my Almodóvar favorite (it also has a gay filmmaker in a complex narrative web).

The Bernard Hermann homage soundtrack composed by Alberto Iglesias (Lovers of the Arctic Circle), and cinematography of Josè Luis Alcaine (The Dancer Upstairs, Belle Epoque, Women on the Verge…) also deserve being singled out for praise.

BTW: My title line disagrees with a statement made early in the proceedings by Enriquè, who may change his mind later, and who, at the end, has used up the erotic charge Angel provided him.

© 2 January 2005, 2017 by Stephen O. Murray