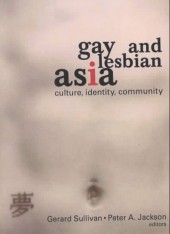

Gay and Lesbian Asia: Culture, Identity, Community

Gay and Lesbian Asia: Culture, Identity, Community

Edited by Peter Jackson and Gerard Sullivan

Published by Routledge

Published 05/10/2001

LGBT Studies (social science)

300 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

Gay and Lesbian Asia: Culture, Identity, Community (2001) brings together overviews, written by insiders, about the status of openly gay and lesbian people in a number of Asian and Pacific Island nations.

Many of the authors are prominent activists within their own societies as well as being explicators of the gains by and obstacles to lesbigay movements in particularly family-oriented societies with unreliable social-insurance nets. Especially vividly informative are the chapters by Heng Hiang Khng on Singapore, Seo Dong-Jin on South Korea, and Wan Yanhai on the PRC. The outstanding contribution by a Westerner to the collection is Chris Berry’s chapter on gay/lesbian identities and Asian families as shown in a number of films and videos.

In general, it seems from what these activists have written here, reflecting on their societies and their personal observations, homosexual behavior can be accommodated; indeed “traditionally” has been. What is far more difficult for families and familistic (Confucian, Muslim, and other) societies to accommodate are exclusive homosexuality and the formation of organizations not under control of either authoritarian governments or patriarchal families. A relationship to a partner may be integrated in the same way as a childless male-female couple is, so long as the same-sex partner is willing to be incorporated as another child/in-law and to demand nothing more than subservience to the greater good of the (extended) family. Procreation is not the only family obligation, and, besides, is one that many gay-identified sons and daughters fulfill.

Developing organizations with more than a few members, disseminating affirmative discourses, claiming physical spaces and open public discussion are major problems for those with “modern” lesbigay identities, despite the diffuse, general prestige of being “modern.” The word “gay” may be appropriated to increase the status of “traditional” gender-variant roles such as the Filipino “bakla,” or the old derogatory contents may be poured into the new label, as seems to be the case for “lesbian” in Japan, the Philippines, and Thailand. More-or-less exclusive, more-or-less non-role-bound homosexuality has “western” models in the experiences of some and imaginations of many more lesbian and gay Asians and Pacific Islanders. The extent to which similar socioeconomic structural changes underlie “modern gay” homosexuality outside “the west,” the extent to which it has diffused through two-way traffic of people and representations, the extent of local modification of the prestige model all remain open questions.

Although history is far from over and no “final” gay or lesbian lifeway is permanently set, this books provides interesting and jargon-free accounts of current situations and changes in process in a number of Asian (and Pacific and Indian Ocean) societies. The primary exception is the very unuseful introduction by Australian co-editor Peter Jackson that offers insupportable interpretations of the legacy of Michel Foucault. (It is a dubious legacy, but not the one Jackson fantasizes!) It is also surprising to see the republication without any notice by Alison Murray of a chapter on Jakarta lesbians with the provocative title “Let them eat Ecstasy.”

Pros: Accounts by Asian gay/lesbian activists about their home societies

Cons: Lack of systematic comparison, obtuse and unhelpful introduction

The Bottom Line: Good beginning to multivocal gay studies

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray