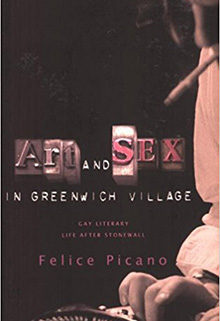

Art and Sex in Greenwich Village

Art and Sex in Greenwich Village

A memoir of gay literary life after Stonewall

by Felice Picano

Published by Basic Books

Published June 28, 2007

History (memoir)

272 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

August 6, 2017

In April 1995 I sent a letter to the Harvard Gay and Lesbian Review reacting to one of Felice Picano’s narcissistic pieces masquerading as “historical corrective”:

Some of the irritation with “the Violet Quill” that Felice Picano complains about (II,2) perhaps stems from the smugness and Manhattan parochialism of its members’ pretentions to have invented “the gay novel” ex nihilo. Even if we exclude the isolation-a-deux novels such as Quatrefoil, Giovanni’s Room, The Fall of Valor, and Two People, in which any gay world is avoided; and the adolescent loves in Aubade, Better Angel, and The City and The Pillar (and others); there were gay novels published by major presses before 1978. I would include the three John Rechy novels focused on homosexuality published during the 1960s by Grove Press, although the protagonists are not gay-identified. Christoper Isherwood’s A Single Man, published by Simon & Schuster in 1964, is unquestionably a gay novel with a self-accepting gay protagonist, as is Merle Miller’s What Happened, published by Harper & Row in 1972. I do not consider any of these earlier novels “pornography or apologia.” They are all set primarily off the island of Manhattan, however, which perhaps explains why they do not count. That the gay novel was invented (or broke through to mainstream publishers) in 1978 is as dubious as that the response to the raid on the Stonewall raid in 1969 was the first instance of gay resistance, protest, or organization.

George Baxt’s first Pharaoh Love mystery, A Queer Kind of Death (1966, which received positive notice in the New York Times; there were 1967 and 1968 sucessors),Gerald Walker’s 1970 novel Cruising, Joseph Hansen’s first three Dave Brandstetter novels (1970–75), and Richard Hall’s 1975 novel The Butterscoth Prince sold well, so I am not sure that even the ’70s New York version of the novel of the doomed homosexual in post-liberation urban milieux first emerged in 1978–9. Clearly Putnam (which published Daniel Curzon’s Something We Do in the Dark in 1971), Dutton (which published Sanford Friedman’s Totempole in 1965), Simon & Schuster, and Harper & Row are at least as “mainstream” as St. Martin’s and Delacorte, and the former four had earlier published less self-hating “gay novels” than Faggots, The Lure, and Dancer from the Dance. As my favorite “Violet Quill” author noted in 1980, New York City is the “media capital of the country and through its hands moves all the hyperfed to the rest of America” (Edmund White, States of Desire, p. 260).

The claim that “we were first,” that “no one had ever gotten away with what I was trying to do: that is, to write and publish a provocative tell-it-like-it-is openly gay novel” is more disingenuous hype. It certainly is not historical correction.

The editor(s) could not find room to published my letter. Since then, the periodical has changed its name but continued to publish historical falsehoods and to reject attempts to correct these. In 2007 Picano published an expansion of his self-glorifying account of gay New York publishing, Art and Sex in Greenwich Village: Gay Literary Life after Stonewall. His nod to “homosexual novels” before Dancer from the Dance (which I do not think includes the word “gay” and is very much a continuation of the doomed fag tradition) expanded to include A Single Man and City of Night, plus Terry Andrews’s The Story of Harold (1974, which Picano tried to republish), Burt Blechman’s Stations, Sanford Friedman’s Totempole (Picano breaks the title into two words), Isherwood’s The World in the Evening (which introduced the word/concept “camp” to mainstream publication), and some of the stories of Tennessee Williams.

Picano (who was born in 1944) has a very high regard to the literary merits and influences of his own publications. He often prefaces mention to any of his own work without prefacing it with something like “critically acclaimed” or “much-praised,” while making the claim that in Ambidextrous (1985) “I’d accomplished a kind of breakthrough in the form” of the memoir. It was not “critically acclaimed” (far from it!) but nonetheless he believes that it “became one of the books that a few generations of lesbian and gay youth read during their coming-out process.”

Most of the way through the book, I feared that the “art” in the title was a self-reference, but eventually there is a full chapter (9) on the cover art for Sea Horse (his own publishing company) and Gay Presses of New York (which included Calamus and JH presses). Though Picano gives himself a lot of credit for choosing the art and doing the production design, there is some discussion of those (including Robert Mapplethorpe) who created the original images used on the covers.

There is surprisingly little about sex (though Picano relates that after photographing his penis, Mapplethorpe ingested it, and that Picano refused to let Allen Ginsberg do that) and not a lot about the gay heyday of the West Village.

The book is not entirely self-absorbed and contains interesting accounts of publishing or trying to publish the young Dennis Cooper, the young Brad Gooch, the young Gavin Dillard, the then-unknown Harvey Fierstein (when he was appearing it what became the first play of Torch Song Trilogy (which became GPNY’s biggest seller), early plays of Doric Wilson and Jane Chambers, the middle-aged Martin Duberman and George Stambolian pivoting to gay studies, the hopelessly befuddled about the business of book-selling James Purdy and Boyd McDonald, the elusive pseudonymous writer who published The Story of Harold (which Picano wanted to republish), the often sloshed but still manipulative Gore Vidal (who played GPNY to get an edition from Vintage of Myra Breckenridge paired with “the dog” Picano considered Myron to be), the evanescent Charles Henri Ford (whom Picano did pin down to reprint the 1933 novel about an already gay Greenwich Village milieu co-written with Parker Tyler, The Young and the Evil) plus control queens Howard Cruse (the graphic novel après la letter, Wendel) and (the much sweeter) Robert Glück (whose New Narrative masterpiece Jack the Modernist that Picano published—though paging through my copy I could not find the photo that Picano says forced changing printers). There are some villains (beyond those not appreciating the genius of Picano’s own writing), notably Duberman’s agent and the publisher of McDonald’s first four books (and the founder of the first company publishing gay literature).

I also found the recounting of learning about the mechanics of manufacturing and distributing books interesting and engaging (with the story of getting included by the distributor Ingram particularly amusing). Gay press barons Chuck Ortleb (Christopher Street, New York Native) and David Goodstein (The Advocate and various skin magazines) get some critical attention. And, of course, there is a rehashing of the fleeting existence of the Lavender Quill monthly gatherings (1980–81) and the destructive George Whitmore, whose collected short fiction remains unpublished (alas).

There are some photographs, including some of the book covers. There is not an index, or even a table of contents. And the book needed a copyeditor to prune repetitions and some fact-checking (Kate Millet did not write Sappho Was a Right-On Woman, there is no such thing as San Francisco Community College, it makes no sense that Franco Zeffirelli adored George Sampson “to the point of producing and directing a whole film—Romeo and Juliet” (wasn’t that Leonard Whiting? Sampson is not even in it), Christopher and His Kind is not a novel and relates more to Goodbye to Berlin than to Down There on a Visit, I don’t think a male can be an ingenue (ingénu, yes)…

Despite my irritation at Picano’s ego, I think he played an important role as a publisher/acquisition editor from 1977 to 1985, the start of a gay publishing boom that did not outlast the twentieth century. His book made me want to read or reread several other books (not those written by him) that he mentions.

And though I despise The Lure, which provided my first exposure to Picano at a San Francisco Gay Academic Union/Walt Whitman Bookstore appearance, I rather like the most narcissistic-titled of his books, Men Who Loved Me. On the sexual culture of clone-era Greenwich Village see Martin P. Levine’s revised NYU Ph.D. dissertation Gay Macho (1998).

©2017, Stephen O. Murray