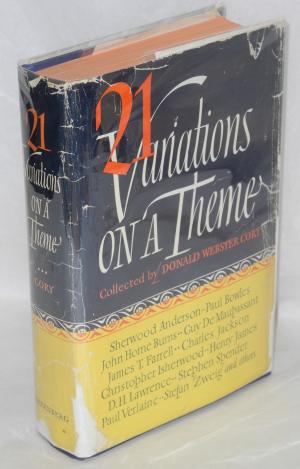

I find Donald Webster Cory’s 1953 collection of 21 Variations on a Theme depressing, aside from the contents of many of the stories (the theme seemingly being not knowing and, generally, struggling to keep from finding out). It had been twelve years since anyone checked it out. (Until this year, I didn’t know it existed myself.) Second, although I recognize some of the names of authors (indeed, half a dozen of the stories appear in more recent collections, such as Edmund White’s), I had no idea that Mark Schorer and Stanley Kauffman wrote fiction. I am sure that very few posties would even recognize their names. I know of them as critics and Schorer as Sinclair Lewis’s biographer. (I’d never heard of Isabel Bolton, Wilson Lehr, Naomi Mitchison, and who today reads Burns, Farrell, or Charles Jackson? The eclipse (during my lifetime, since the book was published in 1953) of reputations is disheartening, especially to someone with considerably less prehumous recognition. And Cory’s unhappiness and turning against gay affirmation is also sad.

Many of the stories are of repressed or suppressed passions, but several provide glimpses of men or women in relationships and supportive networks, as disappointing as this is to would-be opposite sex partners (Maupassant’s “Paul’s mistress” and Wilson Lehr’s “No competition”) or parents (Kauffman’s “Fulvous yellow”). Denton Welch’s “When I was thirteen” contains no guilt, though familial opprobrium there is. Charles Jackson’s narrator in “Palm Sunday” remembers excitement and responsiveness that shocked him as much as the assault of the town artiste/queer (“when my fear turned into something else just as frightening,” p. 130—obviously autobiographical given what comes out in the two novels of his I know). The actors in “No competition,” couturiers in “Fulvous yellow,” and a writer in Schorer’s “Long in populous city pent” are in stereotypical occupations, but this is not the case in Farrell’s “A casual incident” and there seems to be a straight waiter in Stephen Spender’s “Burning cactus.” Astonishingly, the lightest touch belongs to Verlaine (“Charles Husson,” a pimp who goes off with a customer who rejects his female prostitute, who is unable to get the policeman to do anything about it—other than to fuck her).

Jackson’s “Palm Sunday” (his first published story) is especially interesting to me in representing a case in which “everyone in town knew about him” but, generally, no one says the word (p. 134). The very end of “No competition” contains another one (from my birthplace at that: “She shut out of her mind the evil things people used to say about Mr. Gibson [Charles’s great friend at home]. People she knew just didn’t behave like that,” p. 236). Mr. Verne made a “tremendous impression” on the narrator, as did the professor in Stefan Zweig’s “Confusion of sentiment.”

The only deaths are in Lawrence’s “Prussian officer” (for slipping desublimation, not for giving way to passion). I can’t decide whether the adult in Schorer’s story is homophobic. The recollected child was not. He is like Stingo in William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice (which we recently saw again, discovering that Stingo was played by Peter MacNichol, who has since then been a tv lawyer) not understanding what is going on in the glamorous outsiders who entrance him. And there’s lesbian sex in a public lavatory (as in my chapter for Bill’s book, I don’t consider this “public sex,” and it’s certainly not between strangers) in “The knife of the times” by William Carlos Williams!

Thie collection was published two years after The Homosexual in America: A Subjective Approach bylined “Donald Webster Cory,” the pseudonym of future sociologist Edward Sagarin (1913-86, see my chapter on Cory/Sagarin in Vern Bullough (ed.) Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context (2002).

©8 February 1996

©